Despite the tricky names, this topic can actually be simple. Let’s start with an easy breakdown of the two main retirement account types.

401k – This is a retirement account that you set up through work. You can only put money into a 401k account through payroll deductions (taken out of your paycheck before you get paid).

IRA – Individual Retirement Account. This is a retirement account that you set up yourself, not in conjunction with work. You can contribute to this any time and it doesn’t come directly out of your paycheck.

It’s important to know that there are also two different type of tax treatments for each of these accounts: Roth and Traditional. So, there are two different account types and two different tax treatments. This leaves us with 4 different account “styles” that we will address.

Traditional 401k – Pay through your paycheck. Save taxes this year.

Roth 401k – Pay through your paycheck. Save taxes at retirement.

Traditional IRA – Pay after you get your paycheck. Save taxes this year.

Roth IRA – Pay after you get your paycheck. Save taxes at retirement.

The difference between Traditional and Roth is how the taxes are handled. Short version: if it’s traditional, you get tax savings in the year that you contribute. If it’s a Roth, you save in taxes when you retire.

Longer version… stick with me. If this year you made $100,000 and contributed 10% to your Traditional 401k, that’s $10,000 right? Well, when you file your taxes for this year, you get to “deduct” $10,000 from your pay. This means that you don’t pay income taxes on that $10,000. So, if you’re in the 24% income bracket, you save this much: $10,000 x .24 = $2,400. Nice work! Not only did you set aside $10,000 for retirement, but you saved $2,400 in taxes! (This example ignores any other deductions etc. that might apply. It just shows the mechanics.)

Using the same numbers, if you contributed at the same rate to a Roth 401k, you do not get that tax savings when you file your taxes for this year. You’d still have to pay taxes on all $100,000 (Again, oversimplified example, but you get the idea).

The 401k is cool because you contribute money to it automatically through your payroll, so you don’t have to think about it and write a check or intentionally make a transaction every month in order to contribute. You go to your HR department (or online portal, etc.) and just plug in the percentage of your pay that you want to contribute per month (let’s just say 10%). From that point forward, your employer will automatically take 10% of your pay and send it off to your retirement account. Make $5,000 per month? You’ll automatically contribute $500 per month to your 401k. Simple. This is great if you don’t enjoy finance stuff because it can help prevent you from “forgetting” or investing “later.” It’s also cool because it saves money on you taxes. The third reason that makes a 401k cool (and probably the best aspect of it) is that lots of employers will chip in when you chip in. This is often called an employer “match”. This varies greatly by employer so you’re just going to have to check with your HR department. An easy example of a company match might be: your company will match your contributions, dollar for dollar, up to a 5% contribution. What does that mean? It means, if you make $100,000 and contribute 5% ($5,000) throughout the year, your employer will also put in $5,000. Lots of people consider this “free money” and recommend that you should contribute at least up to the point of your employer match. Huh? This means in our above example, if you only contribute $1,000, your employer also only gives you $1,000. That’s $4,000 “free” dollars that you don’t get. So if you are able, it would make sense to contribute at least $5,000 to get the $5,000 “free” dollars.

With an IRA, you contribute directly with money from your bank account. It doesn’t go straight from your paycheck like a 401k. You contribute to it whenever and however much you want (within the IRS limits, which was $6,000 per year in 2019). By contrast, you can contribute $19,000 to a 401k in 2019. An IRA can also help you pay less in taxes. It gives you another option to save for retirement. Let’s say your company doesn’t match or you’re doing a job that doesn’t have a 401k option. You can still set up an IRA. Generally speaking, if your company matches anything, it might be better to start with the 401k. If you have maxed out the 401k contributions, you can then also do an IRA.

Traditional vs Roth. Above, I gave an example of how someone who contributed $10,000 of their $100,000 paycheck to a traditional 401k wouldn’t have to pay taxes on that $10,000, right? And someone who contributed the same amount to a Roth would still have to pay taxes on their whole paycheck, right? Well, savers who use Roth accounts save at retirement. Their contributions are allowed to grow tax free and can be withdrawn and they pay no tax on any of it. Let’s say someone does a one time contribution of $10,000 to a Roth IRA. Then they forget about it and remember when they turn 59.5 years old. Hypothetically, many years have passed and it grew to about $80,000. They get to take that all out and don’t pay any taxes. Meanwhile, their buddy who used a traditional IRA, has to pay taxes on all of his earnings when he withdraws it. He got his tax break years ago when he filed his return that year.

Easy version: if your retirement is soon, a traditional IRA is typically better. If you’re retiring long into the future, a Roth is typical going to to result in a higher total.

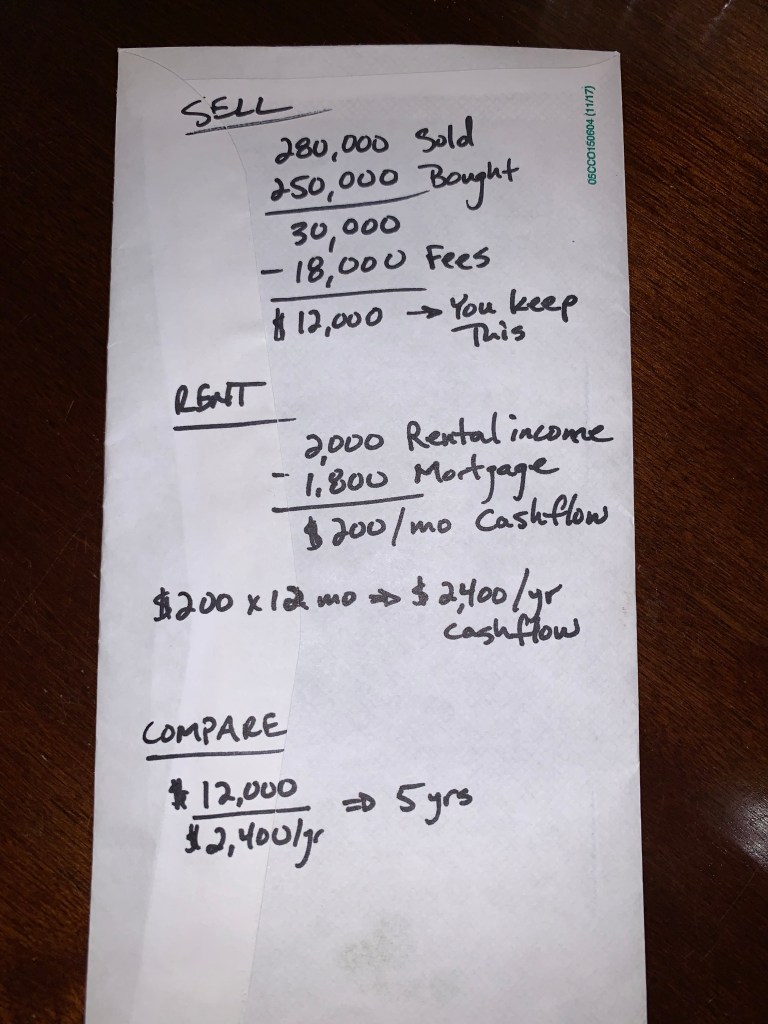

Easy examples: Let’s say that you decide to open a traditional IRA. You would do this by calling the brokerage house of your choice (Vanguard, Fidelity, Schwab, etc.) and they’d be happy to help. Now the account is open and you contribute the maximum for 2019 which is $6,000. If you made $100,000 this year, you get to deduct the $6,000 and you only pay taxes on the remaining $94,000 (assuming you have no other deductions, which is not the case but it’s easier to understand the mechanics this way). The tax rate on those $6,000 would have been 24% but since you contributed those dollars into your traditional IRA, you don’t pay the taxes on that money that year. (Depending on what other deductions you have, you may not be in the 24% tax bracket, but let’s just keep things simple, please.) Back of the envelop math:

$100,000 – $6,000 = $94,000. Then, $6,000 x .24 = $1,440. You saved yourself $1,440 on your taxes this year! Nice work. Important note: when you retire, you will have to pay taxes on the earnings when you take it out, including any growth that you enjoyed. Please keep in mind, this example was for an IRA that you set up on your own. The math is the same for the 401k. The only difference is how you contribute.

Roth IRA example. Your friend, Becky, decides she’s going to set up a Roth IRA the same day that you open your IRA. Interestingly, she also makes exactly $100,000. Weird. She writes a check for $6,000 and sends it into her brokerage, but when she files her taxes, she doesn’t get to subtract that $6,000! Not fair! This is because she contributed to a Roth IRA. The tax savings on Roth accounts comes at retirement. Between now and when Becky retires that $6,000 (and any other contributions that she makes) grows and grows, right? Well, when she takes that money out, Becky doesn’t pay tax on any of it! Given that Becky made the maximum contributions and started early, this could be hundreds of thousands of dollars, or more.

Back of the envelope math. The assumptions are a 30 year old contributes $6,000 at a 10% rate of return and never contributes again. Then retires at 65. The 65 year old is left with $168,614.62. She can take that out and pays no tax. Jackpot!

But what do I put into my 401k or IRA? Whatever you want, generally. Most people stick with a basic S&P 500 Index Fund or something similar. Although, you could just buy one stock and put it all in that. Same with the Roth. For semantics, you don’t truly invest in an IRA or 401k. They are simply accounts which hold your investments. You put money in these accounts and then invest in assets like index funds with the money once it’s in there.

Think of the these accounts like umbrellas. You can put whatever you want underneath them. Stocks, bonds, mutual funds, index funds. Some people even get more creative than that, but we’re keeping it simple. Just know that anything under the umbrella gets a tax benefit.